Predicting Sale Prices Of Houses In Ames

Predicting Sale Prices of Houses in Ames using scikit-learn.

In this tutorial I will discuss how you can go from a raw dataset to a predictive model. For this tutorial we will make use of the Ames Dataset and see whether we can predict house prices based on characteristics provided in the dataset.

The analysis in this tutorial is done in Python using the pandas, scikit-learn and matplotlib packages. We will start by exploring the raw data and see whether we can already see some patterns in the data or that some features should be discarded right away. Next, we will make a straight-forward pipeline that will transform our dataset and fit a linear regression model. Finally, we will evaluate the performance of this model.

I do have limited knowledge with data analysis (I mainly use R), so this tutorial will be most informative for people like me: beginners!

Raw Data & Initial Analysis

First, we need to download the dataset provided in the link above (direct download link here).

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from datetime import date

from sklearn.impute import SimpleImputer

from sklearn.preprocessing import LabelBinarizer, StandardScaler, OneHotEncoder

from sklearn.compose import ColumnTransformer

from sklearn.pipeline import make_pipeline

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

import warnings

# Do not display warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore')

# Import the Ames Housing data (put this in the same folder as your Python file)

house_data = pd.read_csv("AmesHousing.txt", sep="\t")

# I do not like spaces in the column names of a dataset so I first replace spaces

# by underscores

house_data.columns = house_data.columns.str.replace(' ', '_')

Next we want to get a feeling for what exactly we can find in the dataset, so let’s look at some relevant information.

# Get some feeling for the data

print(house_data.head(10))

house_info = house_data.describe()

house_data.info()

Order PID MS_SubClass MS_Zoning Lot_Frontage Lot_Area Street \

0 1 526301100 20 RL 141.0 31770 Pave

1 2 526350040 20 RH 80.0 11622 Pave

2 3 526351010 20 RL 81.0 14267 Pave

3 4 526353030 20 RL 93.0 11160 Pave

4 5 527105010 60 RL 74.0 13830 Pave

5 6 527105030 60 RL 78.0 9978 Pave

6 7 527127150 120 RL 41.0 4920 Pave

7 8 527145080 120 RL 43.0 5005 Pave

8 9 527146030 120 RL 39.0 5389 Pave

9 10 527162130 60 RL 60.0 7500 Pave

Alley Lot_Shape Land_Contour ... Pool_Area Pool_QC Fence \

0 NaN IR1 Lvl ... 0 NaN NaN

1 NaN Reg Lvl ... 0 NaN MnPrv

2 NaN IR1 Lvl ... 0 NaN NaN

3 NaN Reg Lvl ... 0 NaN NaN

4 NaN IR1 Lvl ... 0 NaN MnPrv

5 NaN IR1 Lvl ... 0 NaN NaN

6 NaN Reg Lvl ... 0 NaN NaN

7 NaN IR1 HLS ... 0 NaN NaN

8 NaN IR1 Lvl ... 0 NaN NaN

9 NaN Reg Lvl ... 0 NaN NaN

Misc_Feature Misc_Val Mo_Sold Yr_Sold Sale_Type Sale_Condition SalePrice

0 NaN 0 5 2010 WD Normal 215000

1 NaN 0 6 2010 WD Normal 105000

2 Gar2 12500 6 2010 WD Normal 172000

3 NaN 0 4 2010 WD Normal 244000

4 NaN 0 3 2010 WD Normal 189900

5 NaN 0 6 2010 WD Normal 195500

6 NaN 0 4 2010 WD Normal 213500

7 NaN 0 1 2010 WD Normal 191500

8 NaN 0 3 2010 WD Normal 236500

9 NaN 0 6 2010 WD Normal 189000

[10 rows x 82 columns]

<class 'pandas.core.frame.DataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 2930 entries, 0 to 2929

Data columns (total 82 columns):

Order 2930 non-null int64

PID 2930 non-null int64

MS_SubClass 2930 non-null int64

MS_Zoning 2930 non-null object

Lot_Frontage 2440 non-null float64

Lot_Area 2930 non-null int64

Street 2930 non-null object

Alley 198 non-null object

Lot_Shape 2930 non-null object

Land_Contour 2930 non-null object

Utilities 2930 non-null object

Lot_Config 2930 non-null object

Land_Slope 2930 non-null object

Neighborhood 2930 non-null object

Condition_1 2930 non-null object

Condition_2 2930 non-null object

Bldg_Type 2930 non-null object

House_Style 2930 non-null object

Overall_Qual 2930 non-null int64

Overall_Cond 2930 non-null int64

Year_Built 2930 non-null int64

Year_Remod/Add 2930 non-null int64

Roof_Style 2930 non-null object

Roof_Matl 2930 non-null object

Exterior_1st 2930 non-null object

Exterior_2nd 2930 non-null object

Mas_Vnr_Type 2907 non-null object

Mas_Vnr_Area 2907 non-null float64

Exter_Qual 2930 non-null object

Exter_Cond 2930 non-null object

Foundation 2930 non-null object

Bsmt_Qual 2850 non-null object

Bsmt_Cond 2850 non-null object

Bsmt_Exposure 2847 non-null object

BsmtFin_Type_1 2850 non-null object

BsmtFin_SF_1 2929 non-null float64

BsmtFin_Type_2 2849 non-null object

BsmtFin_SF_2 2929 non-null float64

Bsmt_Unf_SF 2929 non-null float64

Total_Bsmt_SF 2929 non-null float64

Heating 2930 non-null object

Heating_QC 2930 non-null object

Central_Air 2930 non-null object

Electrical 2929 non-null object

1st_Flr_SF 2930 non-null int64

2nd_Flr_SF 2930 non-null int64

Low_Qual_Fin_SF 2930 non-null int64

Gr_Liv_Area 2930 non-null int64

Bsmt_Full_Bath 2928 non-null float64

Bsmt_Half_Bath 2928 non-null float64

Full_Bath 2930 non-null int64

Half_Bath 2930 non-null int64

Bedroom_AbvGr 2930 non-null int64

Kitchen_AbvGr 2930 non-null int64

Kitchen_Qual 2930 non-null object

TotRms_AbvGrd 2930 non-null int64

Functional 2930 non-null object

Fireplaces 2930 non-null int64

Fireplace_Qu 1508 non-null object

Garage_Type 2773 non-null object

Garage_Yr_Blt 2771 non-null float64

Garage_Finish 2771 non-null object

Garage_Cars 2929 non-null float64

Garage_Area 2929 non-null float64

Garage_Qual 2771 non-null object

Garage_Cond 2771 non-null object

Paved_Drive 2930 non-null object

Wood_Deck_SF 2930 non-null int64

Open_Porch_SF 2930 non-null int64

Enclosed_Porch 2930 non-null int64

3Ssn_Porch 2930 non-null int64

Screen_Porch 2930 non-null int64

Pool_Area 2930 non-null int64

Pool_QC 13 non-null object

Fence 572 non-null object

Misc_Feature 106 non-null object

Misc_Val 2930 non-null int64

Mo_Sold 2930 non-null int64

Yr_Sold 2930 non-null int64

Sale_Type 2930 non-null object

Sale_Condition 2930 non-null object

SalePrice 2930 non-null int64

dtypes: float64(11), int64(28), object(43)

memory usage: 1.8+ MB

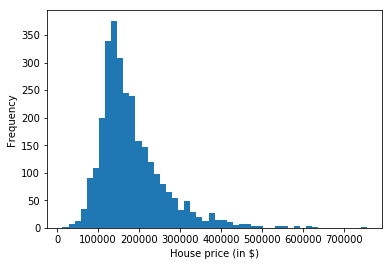

Since we want to build a model that predicts the house price given a set of features of this given house, let’s first check these prices by creating a histogram.

plt.hist(house_data.SalePrice, bins=50)

plt.xlabel("House price (in $)")

plt.ylabel("Frequency")

plt.show()

# Pandas also provides a built-in plotting env

# house_data.SalePrice.plot.hist()

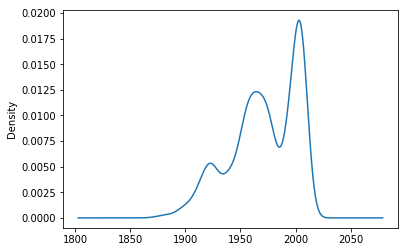

The Year_Built feature would be a candidate to give insights in the sale price of a house. Below we report the density of the year that each house in the dataset is built.

house_data['Year_Built'].plot.kde()

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x1a1ab908d0>

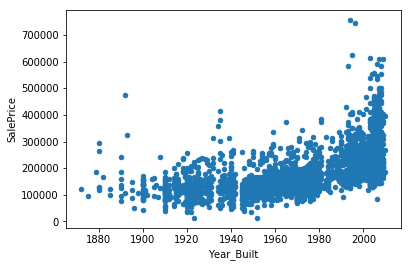

We can check the relationship between the sale price and the year houses are built by creating a scatter plot.

house_data.plot.scatter(x='Year_Built', y='SalePrice')

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x1a19375160>

This plot suggest that houses that are built more recently tend to have a higher sale price (on average). Note that this probably due to the geographical area we are considering. In old cities, like Amsterdam, we can imagine that (part) of the old houses are momumental buildings and therefore have higher sale price.

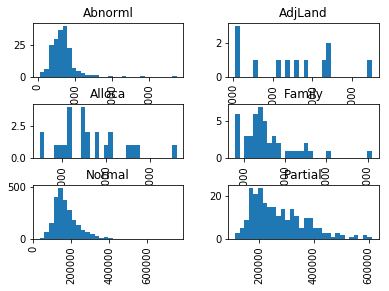

In the analysis above, we have looked into the relationship of the sale price and a numerical feature. A scatter plot is usually a good option to check if there might be an interesting relationship, however for categorical features we need different techniques.

We have information on the type of sale for each house, e.g., some houses are sold with adjecent land, or a family member bought the house. A tool to look at the relationship between this (categorical) feature and the sale price is to look at the histogram for each type of sale condition.

house_data['SalePrice'].hist(by=house_data['Sale_Condition'], bins=30)

array([[<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot object at 0x1a1ad44eb8>,

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot object at 0x1a1acd0f98>],

[<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot object at 0x1a1af29208>,

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot object at 0x1a1a944470>],

[<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot object at 0x1a1ac636d8>,

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot object at 0x1a1ae64940>]],

dtype=object)

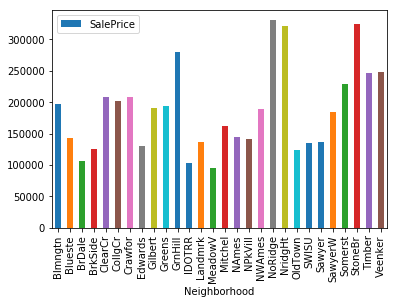

Another feature that is likely to have an influence on the sale price is in what neighbourhood the house is located. We could again create histograms of the sale price for each neighbourhood, but since there are more than 20 neighbourhoods, we can do something else. We take the mean of the sale price for each neighbourhood and present this in a bar plot.

# Check saleprice per neighbourhood

avg_price_neigh = house_data.groupby('Neighborhood').agg({'SalePrice' : 'mean'}).reset_index()

avg_price_neigh.plot.bar(x='Neighborhood', y='SalePrice')

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x1a1b026dd8>

Feature Selection

The dataset provides more than 80 features, and not all features are equally informative for sale price. Selecting good features and transforming existing features is often a rather ad-hoc procedure, since every dataset is unique. However, there are a few standard procedures that usually help in creating a significantly better dataset.

Trimming

One of these techniques is to delete outliers from your dataset. Whether or not this is necesarry also depends on the type of model that is used, e.g., linear models are usually very sensitive to outliers.

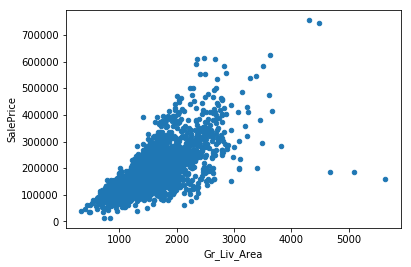

Let’s look at a scatter plot of the living area and sale price.

# Check living space and sale price (there seems to be 5 outliers...)

house_data.plot.scatter(x='Gr_Liv_Area', y='SalePrice')

house_data = house_data.query('Gr_Liv_Area < 4000')

There seem to be 4-5 outliers with very high living areas. For this analysis we will remove these, however if the goal of your model is to also have good predictions for these outliers it might be worthwhile to keep them.

Feature enhancement

There are many ways to enhance existing features. Here, I will show how categorical variables can be improved. To do this, I select all features that are of the type object and save the histogram for these features in a folder figures.

# Check categorical variables and see if we need to delete them

house_data_cat = house_data.select_dtypes(include='object')

for col in house_data_cat.columns:

house_data_cat[col].value_counts().plot.bar(title=col)

plt.savefig('figures/' + col + '_hist.pdf')

plt.clf()

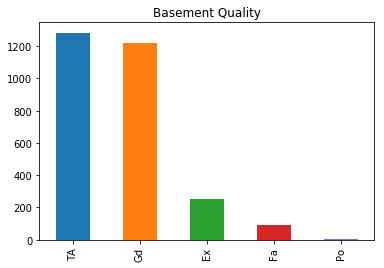

house_data_cat['Bsmt_Qual'].value_counts().plot.bar(title='Basement Quality')

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x1a1d629be0>

There are a considerable number of categorical features that are ordinal, that is, the categories have a certain ordering. In this case, we have information about whether the feature has a value Poor, Fair, Average, Good or Excellent. However, especially the most extreme outcomes are rather unlikely. As we will later see this results in a large number of features (when we one hot encode them) with only minimal extra predictive power. Therefore we combine certain groups.

ord_groups = {'Fa': 'Bad', 'Po': 'Bad', 'TA': 'Average', 'Gd': 'Good', 'Ex':'Good'}

columns_ord = ['Bsmt_Cond', 'Bsmt_Qual', 'Exter_Cond', 'Exter_Qual', 'Fireplace_Qu',

'Garage_Cond', 'Garage_Qual', 'Heating_QC', 'Kitchen_Qual', 'Pool_QC']

for col in columns_ord:

house_data[col].replace(ord_groups, inplace=True)

house_data[col] = house_data[col].astype('category', categories=['Bad', 'Average', 'Good'], ordered=True)

Missing Values

Most real-life datasets have missing values for a subset of its features. There are different ways to deal with these missing values. Usually, when a feature’s value is missing in most of the samples, it is better to just discard them. Let’s see if we have any of these variables.

missing_vals = house_data.isnull().sum(axis = 0)

print(missing_vals)

Order 0

PID 0

MS_SubClass 0

MS_Zoning 0

Lot_Frontage 490

Lot_Area 0

Street 0

Alley 2727

Lot_Shape 0

Land_Contour 0

Utilities 0

Lot_Config 0

Land_Slope 0

Neighborhood 0

Condition_1 0

Condition_2 0

Bldg_Type 0

House_Style 0

Overall_Qual 0

Overall_Cond 0

Year_Built 0

Year_Remod/Add 0

Roof_Style 0

Roof_Matl 0

Exterior_1st 0

Exterior_2nd 0

Mas_Vnr_Type 23

Mas_Vnr_Area 23

Exter_Qual 0

Exter_Cond 0

...

Bedroom_AbvGr 0

Kitchen_AbvGr 0

Kitchen_Qual 0

TotRms_AbvGrd 0

Functional 0

Fireplaces 0

Fireplace_Qu 1422

Garage_Type 157

Garage_Yr_Blt 159

Garage_Finish 159

Garage_Cars 1

Garage_Area 1

Garage_Qual 159

Garage_Cond 159

Paved_Drive 0

Wood_Deck_SF 0

Open_Porch_SF 0

Enclosed_Porch 0

3Ssn_Porch 0

Screen_Porch 0

Pool_Area 0

Pool_QC 2914

Fence 2354

Misc_Feature 2820

Misc_Val 0

Mo_Sold 0

Yr_Sold 0

Sale_Type 0

Sale_Condition 0

SalePrice 0

Length: 82, dtype: int64

Let’s get rid of features that have many missing values.

house_data = house_data.drop(columns=['Alley', 'Fireplace_Qu', 'Pool_QC',

'Misc_Feature', 'Misc_Val'])

For some features a missing value is not really missing, since it can indicate that the value of this feature is zero when it’s missing. Fence and Pool_Area belong to this group. For these features we decide to create a binary variable indicating whether or not the house has this feature (and we do not care about the type or size of feature).

# Make some variables useful

house_data['Fence'] = house_data['Fence'].notna()

house_data['Pool'] = house_data['Pool_Area'] > 0

Similar to the categorical features that are rated from poor until excellent, there are also features with different categories. Again, it might be worthwhile to combine categories in the dataset that only occur a very infrequently. In this case we combine categories that consistute less than 1 percent of the total samples.

house_data_obj = house_data.select_dtypes(include='object')

for col in house_data_obj.columns:

series = house_data[col].value_counts()

mask = (series/series.sum() * 100).lt(1)

house_data[col] = np.where(house_data[col].isin(series[mask].index),'Other',

house_data[col])

house_data[col] = house_data[col].astype('category')

Note that the 1 percent of the total sample is rather ad-hoc. Imagine that you have a dataset consisting of millions of samples, then there is no need to get rid of these categories, since we still have sufficient information (unless you need balanced categories).

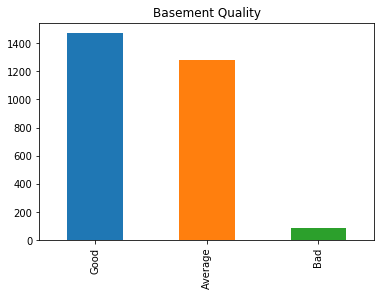

To see what effect our transformations and enhanced have had on our features, we can have a look at the basement quality feature again.

house_data['Bsmt_Qual'].value_counts().plot.bar(title='Basement Quality')

<matplotlib.axes._subplots.AxesSubplot at 0x1a1db4d668>

Data pipeline

Now that we have cleaned and transformed our dataset we can look at if it is possible to create a decent model that can predict sale prices of houses the model has not seen before. However, we first have to deal with a few steps before we can use our dataset in these models.

We need to make sure that we do not evaluate on data that we used to train and estimate our model. So we split our dataset in a training and test part.

X = house_data.drop(columns=['SalePrice'])

y = house_data['SalePrice']

# We need to split the set into a training and test set.

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2)

Imputer

Even though we got rid of the features with many missing values, there are still features that have a few missing values. It is possible to use advanced techiques to “imputate” these missing values, however we will a simple imputing technique, which replaces the missing values with the most frequent value for that feature.

imputer = SimpleImputer(strategy='most_frequent')

Standardisation & Encoding

Most machine learning models require that the scale of the features in the dataset are similar. Therefore, we will standardise all numerical features in the dataset by removing the mean of that feature and dividing by the standard deviation, i.e.,

We also have categorical features which we cannot directly feed to the machine learning models. All features need to be represented by a numerical value. Both nominal and ordinal features can be transformed by a technique called One-hot encoding, where a categorical feature is replaced by a number of dummies that indicate one of these categories.

# Next we need to scale the numerical columns and encode the categorical

# variables. This can be done by splitting the dataset into two parts.

cat_cols = X_train.select_dtypes(include='category').columns

num_cols = X_train.select_dtypes(include='number').columns

cat_cols_mask = X_train.columns.isin(cat_cols)

num_cols_mask = X_train.columns.isin(num_cols)

ct = ColumnTransformer(

[('scale', StandardScaler(), num_cols_mask),

('encode', OneHotEncoder(), cat_cols_mask)])

Note that ordinal values can also be transformed into a single numerical value, where each category is represented by a number that is ordered according to the ordering of these categories. The advantage of this procedure is that we require less features to represent this feature numerically, however for most machine learning models it also results in a linear relationship between the that feature and the feature we want to predict.

Machine learning model

Now that we have a dataset that only consists of numerical values we can apply any machine learning we want. scikit-learn provides many machine learning models with a common interface (except for the hyperparameters), so it is easy to implement many different models. In our case I will only use a linear regression.

linear_reg = LinearRegression()

Combine all steps of pipeline

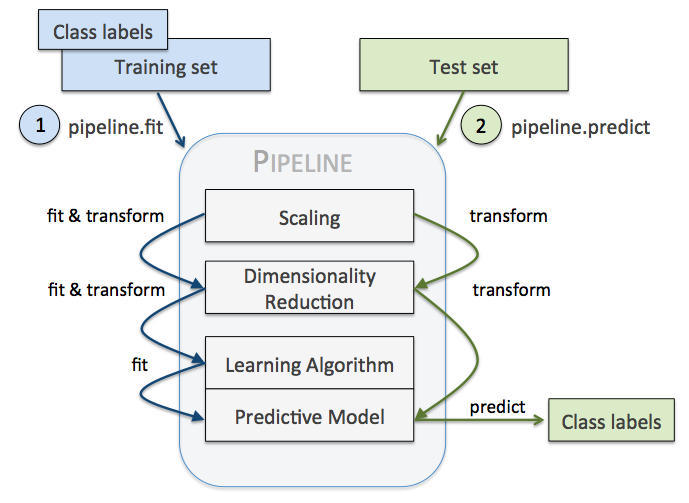

Pipelines can be used to automatically perform all steps of the model estimation (including preprocessing steps). It also makes sure that the preprocessing is done correctly, e.g., the scaling for the test dataset is the one used for the training dataset (Reader: why is this absolutely necessary?). An overview of what the pipeline does is given in the figure below (copyright by Sebastian Raschka).

pipe = make_pipeline(imputer, ct, linear_reg)

Training & Evaluating model

Training the model is as simple as

pipe = pipe.fit(X_train, y_train)

Usually, the best model (within or between) class(es) of models can be determined by using cross-validation or splitting the training dataset into a training and validation part (if you have enough data). I will skip this step and go immediately to the evaluation of our model.

In the step above we estimated and trained our model based on the training set. To see how well it performs we can look at what sale prices our model predict for data it has not seen before.

y_pred = pipe.predict(X_test)

errors = y_pred - y_test

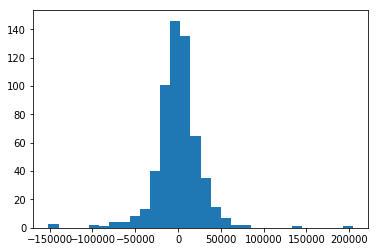

scikit-learn can provide a score for the model, but we will look at the error of the prediction instead. First let’s plot the histogram of the errors

plt.hist(errors, bins=30)

plt.show()

The histogram suggest that the errors are normally distributed (assumption of the linear regression). Furthermore, it seems that most predictions have an error less than 20,000$. To me this seems like a reasonable model.

Conclusion

In this tutorial we have seen how we can go from raw data to a predictive model that has a reasonable performance. However, there are many things we have not discussed yet. To name a few:

- Consider multiple models and select the best one using cross-validation.

- Use a more advanced missing value imputation technique, e.g., MICE.